The 'death gap' and the choice of a female biomedical scientist

Pursuing a largely unexplored field of research, the scientist and her colleagues are among the pioneers in Vietnam working to prevent deadly fungal diseases that often go undetected within the community.

It was the last day of 2017. The journey from Incheon International Airport in Seoul, South Korea, to Tan Son Nhat Airport in Ho Chi Minh City took about five hours, and the Boeing 737 was preparing to land. Through the small window framed by patches of white cloud, Dr. Duong Nu Tra My looked down at her homeland after seven years away and asked herself: “Is it a right decision to return to Vietnam or a mistake that I’ll regret? “

Dr. Duong Nu Tra My

2.5% of Vietnamese face risk of fungal disease

Was born in Phu Yen, a coastal province in south-central Vietnam, Dr. Tra My learned to be independent from a young age. In sixth grade, she moved alone to downtown Tuy Hoa to pursue better educational opportunities. When it was time to pick a major, she went against her parents' wishes, who wanted her to study pharmacy or economics. Instead, she was captivated by biotechnology – a field that would allow her to explore the microscopic world and understand how pathogens cause disease in humans. "It would’ve been boring to follow the beaten path. I wanted to learn something new", Dr. My recalled.

After graduating from Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology, she earned a dual scholarship from Chonnam National University (CNU) and the Brain Korea 21 (BK21) Research Fund, allowing her to pursue a Master’s degree and later a PhD in Molecular Medicine. At the time, South Korea's biomedical research sector was booming, largely due to significant funding from major corporate conglomerates.

During her studies in South Korea, Tra My had the opportunity to delve into pathogenic bacteria and explore immunotherapy approaches in cancer prevention and treatment. Upon returning to Vietnam, she shifted her research focus to fungal pathogens—a concept still unfamiliar to much of the public.

“Fungi aren’t entirely new to science,” she explained. “But research on fungi that cause disease in humans still faces significant gaps and challenges.” She pointed to the growing issue of drug resistance, noting that while people often associate it with bacteria, fungi are also dangerous pathogens subjected to similar selective pressures.

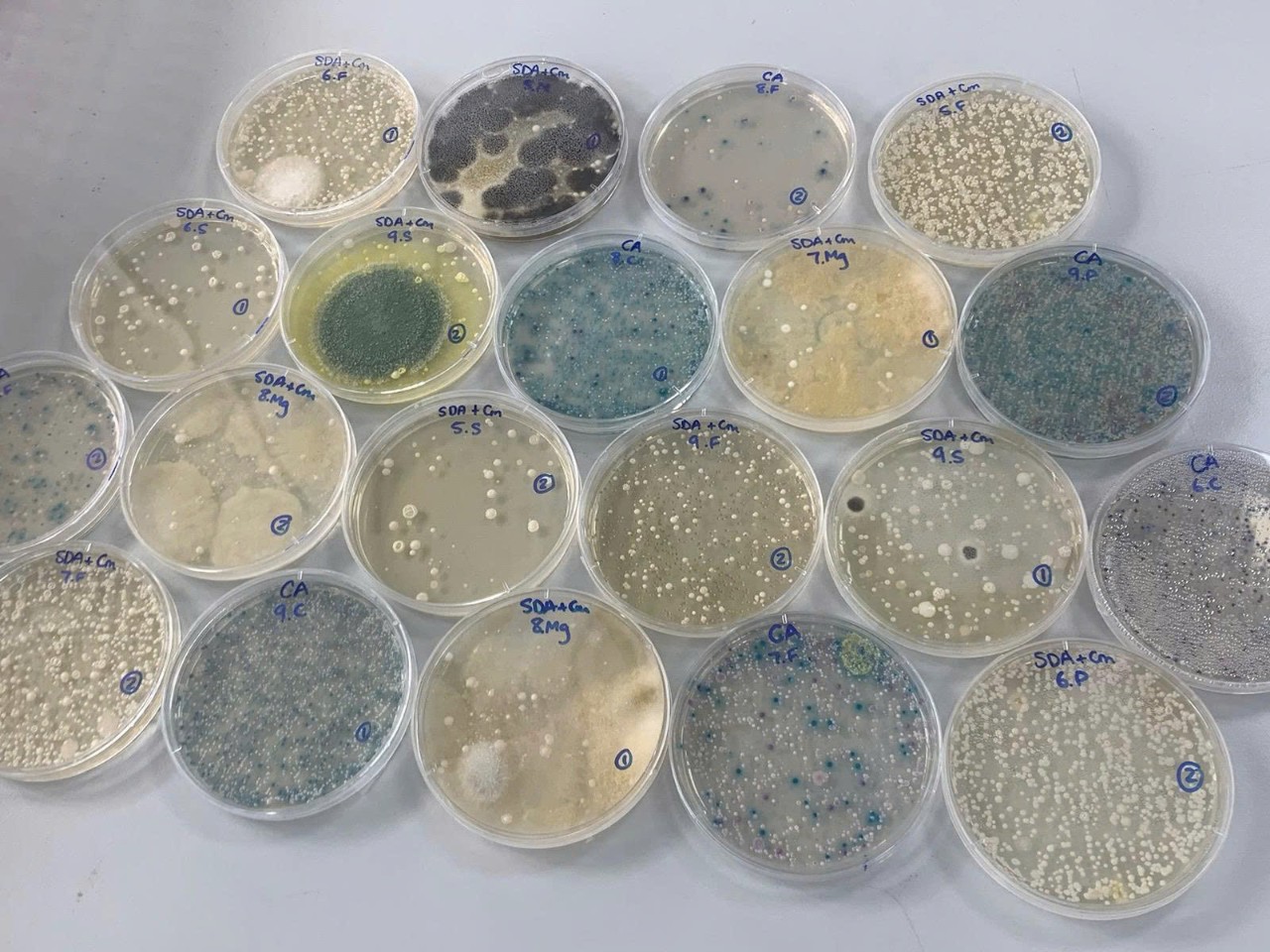

Fungi isolated at the Joint HMu-Usyd lab

According to published scientific studies, over 300 million people worldwide are affected by fungal diseases each year. Of those, an estimated 6.5 million cases involve invasive fungal infections, leading to approximately 3.8 million deaths annually. Fungal infections now rank as the fifth leading cause of death globally – surpassing both tuberculosis and malaria.

At least 2.5% of Vietnamese people are at risk of fungal infections

In a 2020 scientific publication on the burden of fungal diseases in Vietnam, she and her colleagues identified Aspergillus as the leading fungal pathogen in the country, responsible for over 115,000 cases of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and 23,000 cases of invasive aspergillosis annually. Without treatment, chronic pulmonary aspergillosis carries a five-year mortality rate of nearly 50%. Invasive aspergillosis is even more severe, with mortality rates ranging from 30% to 80%. Alarmingly, if left untreated, invasive aspergillosis is almost always fatal – 100% of patients are expected to die within just 30 to 90 days. Yet despite its severity, diagnosis rates remain strikingly low – only about 1 in 1,000 cases are correctly identified – indicating a vast number of undiagnosed and untreated patients. Fungal lung infections remain a critical blind spot in Vietnam’s healthcare system, as many hospitals and medical facilities still lack the capacity for proper diagnosis.

The threat caused by humans themselves

Under the pressure of natural selection, fungi are evolving to better adapt to their environment. The overuse of antifungal agents in agriculture has accelerated the emergence of drug-resistant fungal strains. According to several farmers in Ca Mau, Vietnam, they admit to using antifungal chemicals in hopes of boosting crop and livestock yields by up to 30%.

The relentless race for higher productivity has driven farmers to use anti-fungal agents indiscriminately and without proper regulation. This has inadvertently allowed fungi to begin adapting and developing resistance to these drugs. Initially, fungi developed resistance mechanisms only against antifungal treatments used in animals. However, the subsequent emergence of cross-resistance is a growing concern. Cross-resistance occurs when antifungal drugs used in livestock and crops share similar molecular structures or origins with those used in human medicine. In such cases, fungi gradually adapt through natural selection and evolve to resist human antifungal treatments as well.

Dr. Tra My and colleagues in research on Aspergillus fungi in the Mekong Delta region.

In 2018, Dr. My’s research team conducted a study assessing azole resistance in Aspergillus fungi. They collected soil, water, and air samples from 150 sites across five agricultural regions in Ca Mau. The results revealed azole resistance rates as high as 50% - a staggering figure compared to the 10% threshold already considered alarmingly high in many other countries.

In Vietnam, where smoking rates are high, environmental pollution is widespread, and the burden of tuberculosis remains significant, Dr. My and her colleagues note that patients with a history of pulmonary tuberculosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) face an increased risk of developing pulmonary aspergillosis. Limited diagnostic capacity for fungal infections often leads to misdiagnosis, with many cases mistaken for tuberculosis relapse. This results in prolonged and inappropriate treatment, increasing costs and the risk of drug resistance among patients.

The emergence of drug-resistant fungal strains poses a particularly serious threat to individuals with weakened immune systems, including patients with HIV/AIDS, diabetes, cancer, long-term corticosteroid users, and those taking immunosuppressive medications.

Meanwhile, the cost of treating certain fungal infections poses a significant financial burden. On average, an invasive Candida infection can cost around $65,000 USD (nearly 1.7 billion VND), while treatment for mucormycosis can reach up to $110,000 USD (2.9 billion VND).

A troubling reality is that only three classes of antifungal drugs are currently approved for treating fungal diseases—and several of these are in short supply in Vietnam. This means that even patients with the financial means may still be unable to access life-saving medication in time.

The hope driving a scientist forward

A lack of data on fungal infections in the community, gaps in diagnosis and treatment, and the financial burden on patients are what have driven the female scientist to pursue mycology over the past seven years. She previously worked at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research before taking on her current role as Head of the Microbiology Laboratory at the University of Sydney Vietnam Institute.

After years of training in developed countries, the question of “To stay abroad or return home?” is a deeply personal and difficult one faced by many young scientists at the start of their careers. For Tra My, returning to Vietnam was not merely a choice – it was a commitment. A commitment to contribute to her homeland, where she believes science holds the power to bring about meaningful change.

Being able to continue pursuing my research passion on my homeland, and witnessing the transformation of science and technology in Vietnam – this brings me true happiness,

In 2021, Dr. My joined a global initiative led by the World Health Organization (WHO) to develop the “Fungal Priority Pathogens List.” Over the course of a year, she and an international team of experts diligently sifted through tens of thousands of scientific documents to identify 19 major disease-causing fungal species. The resulting list serves as a foundational reference, guiding future research as well as global public health strategies.

Dr Tra My led a practical lab training session on Aspergillus diagnostics at the National Lung hospital

In 2019 and 2022, Dr. My and her colleagues organized a series of training programs to enhance the diagnostic capacity for fungal infections among healthcare professionals in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. Beyond education, she has also served as a key connector – bridging local and international experts to launch several in-depth research projects on human-pathogenic fungi in Vietnam. These efforts are helping to lay a strong scientific foundation aimed at improving the diagnosis and treatment of fungal diseases nationwide, reducing costs, enhancing treatment outcomes, and ultimately increasing patients’ chances of survival.

Over the past several years at the University of Sydney Vietnam Institute, Dr. Tra My has continuously expanded her research scope to include a variety of pathogenic fungal species, driven by a desire to better understand this silent yet increasingly prevalent “killer.” Central to her approach is the interdisciplinary “One Health” strategy, which she and her team have actively applied to comprehensively assess the risk of disease transmission throughout the food supply chain – from farm to table.

“Could pathogenic agents present on farms travel along the food supply chain and impact human health?” is the question that the research team is striving to answer. In particular, they focus on the risks posed by drug-resistant fungal strains – a growing threat amid the rising prevalence of chronic diseases.

Dr. Tra My and colleagues in research on pathogenic fungi in the Northern region.

Currently, the “One Health” strategy is supported by key agencies such as the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Industry and Trade, and Ministry of Agriculture and Environment, working together to control the overuse of drugs in agriculture – an underlying cause of rising antimicrobial resistance. According to Dr. Tra My, tracing the entire supply chain enables the research team to clarify many issues and deliver timely, strong warnings to relevant authorities. “Increasing productivity is necessary, but it must be sustainable,” she emphasized.

Looking ahead, Dr. Tra My shared that she is enhancing her laboratory staff’s capabilities through ongoing training programs, preparing her team to take on increasingly complex research projects in the near future. Additionally, through the state-of-the-art laboratory at the University of Sydney Vietnam Institute, she and her colleagues aim to support researchers both domestically and internationally, while strengthening professional assistance for grassroots healthcare – an area in urgent need of scientific support.

“Each study we conduct has been and continues to answer unresolved questions for the community. Finding those answers gives scientists like me a profound sense of purpose in our work,” said Dr. Duong Nu Tra My./